Novi Sad

| City of Novi Sad Град Нови Сад Grad Novi Sad Újvidék város Mesto Nový Sad Город Нови Сад |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| — City — | |||

|

|||

|

|||

| Nickname(s): Serbian Athens | |||

|

|||

| Coordinates: | |||

| Country | |||

| Province | |||

| District | South Bačka | ||

| Municipalities | 2 | ||

| Founded | 1694 | ||

| City status | 1 February 1748 | ||

| Government | |||

| - Mayor | Igor Pavličić (DS) | ||

| Area | |||

| - City | 699 km2 (269.9 sq mi) | ||

| - Urban | 129.4 km2 (49.9 sq mi) | ||

| Elevation | 80 m (262 ft) | ||

| Population (2010)[1] | |||

| - City | 372,999 | ||

| - Urban | 286,157 | ||

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | ||

| - Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | ||

| Postal code | 21000 | ||

| Area code(s) | +381(0)21 | ||

| Car plates | NS | ||

| Website | www.novisad.rs | ||

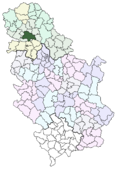

Novi Sad (Serbian Cyrillic: Нови Сад, pronounced [nóviː sâːd] (![]() listen); Hungarian: Újvidék; Slovak: Nový Sad; Rusyn: Нови Сад) is the capital[2] of the northern Serbian province of Vojvodina, and the administrative centre of the South Bačka District. The city is located in the southern part of Pannonian Plain on the Danube river.

listen); Hungarian: Újvidék; Slovak: Nový Sad; Rusyn: Нови Сад) is the capital[2] of the northern Serbian province of Vojvodina, and the administrative centre of the South Bačka District. The city is located in the southern part of Pannonian Plain on the Danube river.

Novi Sad is Serbia's second largest city, after Belgrade.[3][4] According to the data from August 2010, the city has an urban population of 286,157, while its municipal population was 372,999.[1] It is located on the border of the Bačka and Srem regions, on the banks of the Danube river and Danube-Tisa-Danube Canal, while facing the northern slopes of Fruška Gora mountain.

The city was founded in 1694, when Serb merchants formed a colony across the Danube from the Petrovaradin fortress, Austro-Hungarian strategic military post. In 18th and 19th centuries, it became an important merchant and manufacturing centre. After destruction in the 1848 Revolution, it was restored, and emerged as a centre of Serbian culture of that period, earning the nickname Serbian Athens. During the history, it maintained multi-cultural identity, with Serbs, Hungarians and Germans being the main ethnic groups. Today, Novi Sad is a large industrial and financial centre of the Serbian economy.

Contents |

Name

The name Novi Sad means "New Plantation" (noun) in Serbian. Its Latin name, stemming from establishment of city rights, is "Neoplanta". The official names of Novi Sad used by the local administration are:

In both Croatian and Romanian, which are official in the provincial administration, the city is called "Novi Sad". Historically, it was also called "Neusatz" in German.

In its wider meaning, the name Grad Novi Sad refers to the "City of Novi Sad", which is one of the city-level administrative units of the Republic of Serbia. Novi Sad could also refer strictly to the urban part of the City of Novi Sad (including "Novi Sad proper", and towns of Sremska Kamenica and Petrovaradin), as well as only to the historical core on the left Danube bank, i.e. "Novi Sad proper" (excluding Sremska Kamenica and Petrovaradin).

History

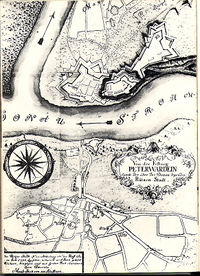

Origins

Human settlement in the territory of present-day Novi Sad has been traced as far back as the Stone Age (about 4500 BC). This settlement was located on the right bank of the river Danube in the territory of present-day Petrovaradin. This region was conquered by Celts (in the 4th century BC) and Romans (in the 1st century BC). The Celts founded the first fortress at this location, which was located on the right bank of the Danube. During Roman rule, a larger fortress was built in the 1st century with the name Cusum and was included into Roman province of Pannonia. In the 5th century, Cusum was devastated by the invasion of the Huns.

By the end of the 5th century, Byzantines had reconstructed the town and called it by the names Cusum and Petrikon. The town was later conquered by Ostrogoths, Gepids, Avars, Franks, Bulgarians, and again by Byzantines. The region was conquered by the Kingdom of Hungary between the 10th and 12th century, and the town was mentioned under the name Bélakút or Peturwarad (Pétervárad, Serbian: Petrovaradin) in documents from 1237. In the same year (1237), several other settlements were mentioned to exist in the territory of modern urban area of Novi Sad (on the left bank of the Danube).

From 13th to 16th century, these settlements existed in the territory of modern urban area of Novi Sad:[5][6]

- on the right bank of the Danube: Pétervárad (Serbian: Petrovaradin) and Kamanc (Serbian: Kamenica).

- on the left bank of the Danube: Baksa or Baksafalva (Serbian: Bakša, Bakšić), Kűszentmárton (Serbian: Sent Marton), Bivalyos or Bivalo (Serbian: Bivaljoš, Bivalo), Vásárosvárad or Várad (Serbian: Vašaroš Varad, Varadinci), Zajol I (Serbian: Sajlovo I, Gornje Sajlovo, Gornje Isailovo), Zajol II (Serbian: Sajlovo II, Donje Sajlovo, Donje Isailovo), Bistritz (Serbian: Bistrica).

Some other settlements existed in the suburban area of Novi Sad: Mortályos (Serbian: Mrtvaljoš), Csenei (Serbian: Čenej), Keménd (Serbian: Kamendin), Rév (Serbian: Rivica).

Etymology of the settlement names show that some of them are of Hungarian origin (for example Bélakút, Baksafalva, Kűszentmárton, Vásárosvárad, Rév), which indicate that some of them were initially inhabited by Hungarians before the Ottoman invasion.[6] Some settlement names are of Slavic origin, and for some exact origin is not certain. For example, Bivalo (Bivaljoš) was a large Slavic settlement that dates from the 5th-6th century.[5]

Tax records from 1522 are showing a mix of Hungarian and Slavic names among inhabitants of these villages, including Slavic names like Bozso (Božo), Radovan, Radonya (Radonja), Ivo, etc. Following the Ottoman invasion in the 16th-17th century, some of these settlements were destroyed and most Hungarian inhabitants have left this area. Some of the settlements also existed during the Ottoman rule, and were populated by ethnic Serbs.

Between 1526 and 1687, the region was under Ottoman rule. In the year 1590, population of all villages that existed in the territory of present-day Novi Sad numbered 105 houses inhabited exclusively by Serbs. However, Ottoman records mention only those inhabitants that paid taxes, thus the number of Serbs that lived in the area (for example those that served in the Ottoman army) was larger.[7]

The founding of Novi Sad

At the outset of Habsburg rule near the end of the 17th century, people of Orthodox faith were forbidden from residing in Petrovaradin, thus Serbs were largely unable to build homes there. Because of this, a new settlement was founded in 1694 on the left bank of the Danube. The initial name of this settlement was Serb City (Ratzen Stadt). Another name used for the settlement was Petrovaradinski Šanac. In 1718, the inhabitants of the village of Almaš were resettled to Petrovaradinski Šanac, where they founded Almaški Kraj ("the Almaš quarter").

According to 1720 data, the population of Ratzen Stadt was composed of 112 Serbian, 14 German, and 5 Hungarian houses. The settlement officially gained the present name Novi Sad (Neoplanta in Latin) in 1748 when it became a "free royal city".

The edict that made Novi Sad a "free royal city" was proclaimed on 1 February 1748. The edict reads:

"We, Maria Theresa, by the mercy of God Holy Roman Empress,

Queen of Hungary, Bohemia, Moravia, Dalmatia, Croatia, Slavonia, Rama, Serbia, Galicia, Lodomeria, Carinthia, etc, etc.

cast this proclamation to anyone, whom it might concern...so that the renowned Petrovaradinski Šanac, which lies on the other side of the Danube in the Bačka province on the Sajlovo land, by the might of our divine royal power and prestige...make this town a Free Royal City and to fortify, accept and acknowledge it as one of the free royal cities of our Kingdom of Hungary and other territories, by abolishing its previous name of Petrovaradinski Šanac, renaming it Neoplantae (Latin), Új-Vidégh (Hungarian), Neusatz (German) and Novi Sad (Serbian)."

For much of the 18th and 19th centuries, Novi Sad was the largest city in the world populated by ethnic Serbs. The reformer of the Serbian language, Vuk Stefanović Karadžić, wrote in 1817 that Novi Sad is the "largest Serb municipality in the world". It was a cultural and political centre of Serbs, who did not have their own national state at the time. Because of its cultural and political influence, Novi Sad became known as the Serbian Athens (Srpska Atina in Serbian). According to 1843 data, Novi Sad had 17,332 inhabitants, of whom 9,675 were Orthodox Christians, 5,724 Catholics, 1,032 Protestants, 727 Jews, and 30 adherents of the Armenian church. The largest ethnic group in the city were Serbs, and the second largest were Germans.

During the Revolution of 1848-1849, Novi Sad was part of Serbian Vojvodina, a Serbian autonomous region within the Habsburg Empire. In 1849, the Hungarian army located on the Petrovaradin Fortress bombarded and devastated the city, which lost much of its population. According to an 1850 census there were only 7,182 citizens in the city compared with 17,332 in 1843. Between 1849 and 1860, the city was part of a separate Austrian crownland known as the Vojvodina of Serbia and Tamiš Banat. After the abolishment of this province, the city was included into Bačka-Bodrog County.

After 1867, Novi Sad was located within the Hungarian part of Austria-Hungary. During this time, the Magyarization policy of the Hungarian government drastically altered the demographic structure of the city, i.e. from the predominantly Serbian, the population of the city became ethnically mixed.

After the First World War

On 25 November 1918, the Assembly of Serbs, Bunjevci, and other nations of Vojvodina in Novi Sad proclaimed the union of Vojvodina region with the Kingdom of Serbia. Since 1 December 1918, Novi Sad is part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes; and in 1929, Novi Sad became the capital of the Danube Banovina, a province of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

In 1941, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was invaded and partitioned by the Axis powers, and its northern parts, including Novi Sad, were annexed by Hungary. During World War II, about 5,000 citizens were murdered and many others were resettled. In three days of Novi Sad raid (21—23 January 1942) alone, Hungarian police killed 1,246 citizens, among them more than 800 Jews, and threw their corpses into the icy waters of the Danube, while the total death toll of the raid was around 2,500.[8][9] Citizens of all nationalities - Serbs, Hungarians, Slovaks, and others - fought together against the Axis authorities.[9] In 1975 the whole city was awarded the title People's Hero of Yugoslavia.

The communist partisans from Syrmia and Bačka entered the city on 23 October 1944 under the leadership of Todor Gavrilovics Rilc. During the Military administration in Banat, Bačka and Baranja (October 17, 1944 - January 27, 1945), the communist partisans killed one number of citizens who were seen as Axis collaborators or threat to the new regime. According to article in Večernje novosti from June 9, 2009, most of the people killed by the partisans in Novi Sad were ethnic Serbs.[10] Partisans also killed some citizens of Hungarian and German ethnicity. According to some sources, during this period about 2,000[11]-10,000[12] citizens (including 3 Hungarian priests[13]) were killed.

Novi Sad became part of the new socialist Yugoslavia. Since 1945, Novi Sad has been the capital of Vojvodina, a province of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and Serbia. The city went through rapid industrialization and its population more than doubled in the period between World War II and the breakup of Yugoslavia. After 1992, Novi Sad was part of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, which, in 2003, was transformed into the State Union of Serbia and Montenegro. Since 2006, Novi Sad is part of an independent Serbia.

Devastated by NATO bombardment, during the Kosovo War of 1999, Novi Sad was left without all of its three Danube bridges, communications, water, and electricity. Residential areas were cluster bombed several times while its oil refinery was bombarded daily, causing severe pollution and widespread ecological damage (see: 1999 NATO bombing in Novi Sad).

Geography

Novi Sad is located in the northern Serbian province of Vojvodina, with land area of 699 km²,[14] while on the city's official site, land area is 702 km²;[15] and the urban area is 129.7 km².[15] The city lies on the river Danube and one small section of the Danube-Tisa-Danube Canal.

Novi Sad's landscape is divided into two parts, one is situated in the Bačka region and another in the Syrmia region. The river Danube is a natural border between them. Bačka's side of the city lies on one of the southern lowest parts of Pannonian Plain, while Fruška Gora's side (Syrmia) is a horst mountain. Alluvial plains along Danube are well formed, especially on the left bank, in some parts 10 km from the river. A large part of Novi Sad lies on a fluvial terrace with an elevation of 80–83 m (262.47–272.31 ft). The northern part of Fruška Gora is composed of massive landslide zones, but they are not active, except in the Ribnjak neighborhood (between Sremska Kamenica and Petrovaradin Fortress).[16]

Climate

Novi Sad has a moderate continental climate, with four seasons. Autumn is longer than spring, with long sunny and warm periods. Winter is not so severe, with an average of 22 days of complete sub-zero temperature. January is the coldest month, with an average temperature of −1.9 °C (28.6 °F). Spring is usually short and rainy, while summer arrives abruptly. The coldest temperature ever recorded in Novi Sad was −30.7 °C (−23.3 °F) on 24 January 1963; and the hottest temperature ever recorded was 41.6 °C (106.9 °F) on 24 July 2007.[17]

The southeast-east wind Košava, which blows from the Carpathians and brings clear and dry weather, is characteristic of the local climate. It mostly blows in autumn and winter, in 2–3 days intervals. The average speed of Košava is 25–43 km per hour but certain strokes can reach up to 130 km/h. In winter time, followed by a snow storm, it can cause snowdrifts. Also it can cause temperatures to drop to around −30 °C (−22 °F).

| Climate data for Rimski Šančevi, Novi Sad | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Source: [18] | |||||||||||||

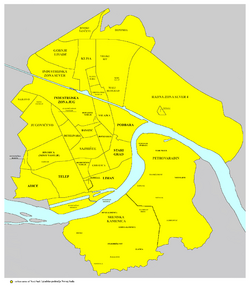

Cityscape

The urban area of Novi Sad has a population of 216,583 and is generally divided into three parts: "Novi Sad proper" (with population of 191,405), situated on the left bank of the Danube, and Petrovaradin (with population of 13,973) and Sremska Kamenica (with population of 11,205), on the right bank of the Danube.

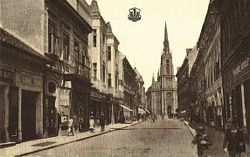

Novi Sad is a typical Central European town. There are only a few buildings dating before 19th century, because the city was almost totally destroyed during the 1848/1849 revolution, so the architecture from 19th century dominates the city centre. Around the center, old small houses used to dominate the cityscape, but they are being replaced by modern multi-story buildings.

During the socialist period, new blocks with wide streets and multi-story buildings were built around the city core. However, not many communist-style high-rise buildings were built, and the total number of 10+ floor buildings remained at 40-50, most of the rest being 3-6 floor Apartment buildings. City's new boulevard (today's Bulevar oslobođenja) was cut through the old housings in 1962-1964, establishing major communication lines. Several more boulevards were subsequently built in a similar manner, creating an orthogonal network over what used to be mostly radial structure of the old town. Those interventions paved the way for a relatively unhampered growth of the city, which almost tripled its population since the 1950s, and traffic congestions (except on a few critical points) are still relatively mild despite the huge boost of car numbers, especially in later years.

Neighborhoods

Some of the oldest neighborhoods in the city are Stari Grad (Old Town), Rotkvarija, Podbara and Salajka which merged in 1694, in the time when the city was formed. Sremska Kamenica and Petrovaradin, on the right bank of the Danube, were separate towns in the past, but today are parts of the urban area of Novi Sad. Liman (divided into four parts, numbered I-IV), as well as Novo Naselje are neighborhoods built during 1960s, 1970s and 1980s with modern buildings and wide boulevards.

New neighborhoods, like Liman, Detelinara and Novo Naselje, with modern high residential buildings emerged from fields and forests surrounding the city to house the huge influx of people from the countryside following the World War II. Many old houses in the city centre, Rotkvarija and Bulevar neighborhoods were torn down in the 1950s and 1960s to be replaced with multi-story buildings, as the city experienced a major construction boom during the last 10 years; some neighborhoods, like Grbavica have completely changed their face.

Neighborhoods with newer individual housing are mostly located away from the city center; Telep in the southwest is the oldest such quarter, while Klisa on the north, as well as Adice, Veternička Rampa and Veternik on the west significantly expanded during last 15 years, partly due to an influx of Serb refugees during the Yugoslav wars.

Suburbs and villages

Besides the urban part of the city (which includes Novi Sad proper, with population of 255,339, Petrovaradin (16,817) and Sremska Kamenica (12,660)), there are 12 more settlements and 1 town in Novi Sad's municipal area.[1] 23.7% of total City's population live in suburbs, the largest being Futog (20,558), and Veternik (16,833) on the West, which over the years, especially in the 1990s, have grown and physically merged to the city.

The most isolated and the least populated village in the suburban area is Stari Ledinci (823). Ledinci, Stari Ledinci and Bukovac are located on Fruška Gora slopes and the last two have only one paved road, which connect them to other places. Besides the urban area of Novi Sad, the suburb of Futog is also officially classified as "urban settlement" (a town), while other suburbs are mostly "rural" (villages).

Some towns and villages in separate municipalities of Sremski Karlovci, Temerin and Beočin which border City of Novi Sad, share the same public transportation and are also economically connected to Novi Sad.

Kamenica

Ledinci

●●●●●

Novi Sad

| No. | Name | Town or village | Urban municipality | Population[1](2009 data) |

| 1 | Begeč | village | Novi Sad | 3,502 |

| 2 | Budisava | village | Novi Sad | 4,004 |

| 3 | Bukovac | village | Petrovaradin | 4,049 |

| 4 | Čenej | village | Novi Sad | 2,134 |

| 5 | Futog | town | Novi Sad | 20,378 |

| 6 | Kać | village | Novi Sad | 12,499 |

| 7 | Kisač | village | Novi Sad | 5,566 |

| 8 | Kovilj | village | Novi Sad | 5,612 |

| 9 | Ledinci | village | Petrovaradin | 1,881 |

| 10 | Rumenka | village | Novi Sad | 6,485 |

| 11 | Stari Ledinci | village | Petrovaradin | 926 |

| 12 | Stepanovićevo | village | Novi Sad | 2,216 |

| 13 | Veternik | village | Novi Sad | 16,503 |

Politics

Novi Sad is the main administrative centre of the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina, and as such, is home to Vojvodina's Executive Council and Provincial Assembly.

The city's administration bodies consist of city assembly as representative body, mayor and city government as executive body. Members of the city assembly and mayor are elected at direct elections. City assembly has 78 seats, while city government has 11 members. The mayor and members of city's assembly are elected to four-year terms; and city government is elected on mayor’s proposal by the city assembly by majority of votes.

As of 2008 election, mayor of Novi Sad is Igor Pavličić (Democratic Party); while in the city assembly majority have Democratic Party, G17+, Together for Vojvodina and Hungarian Coalition.

Since 2002, when the new statute of Novi Sad came into effect, City of Novi Sad is divided into 46 local communities within two urban municipalities, Novi Sad and Petrovaradin, whose borders are defined by geographic boundaries (Danube river).

International relations

Twin towns — Sister cities

Novi Sad has relationships with several twin towns. One of the main streets in its city centre is named after Modena in Italy; and likewise Modena has named a park in its town centre Parco di Piazza d'Armi Novi Sad. The Novi Sad Friendship Bridge in Norwich, United Kingdom, by Buro Happold, was also named in honour of Novi Sad. Besides twin cities, Novi Sad has many signed agreements on joint cooperation with many European cities (see also: Twin cities of Novi Sad). As of 2006[update], Novi Sad's twin towns are:

|

Demographics

| Demographics of Novi Sad | ||

|---|---|---|

| 2002 census | Municipal area | Novi Sad proper |

| Total population | 299,294 | 191,405 |

| Serbs | 76.73% | 76.15% |

| Hungarians | 5.24% | 6.03% |

| Yugoslavs | 3.17% | 3.69% |

| Slovaks | 2.41% | n/a |

| Croats | 2.09% | 1.84% |

| Others | 9.91% | 12.31% |

Novi Sad is the largest city in Vojvodina, and second largest in Serbia (after Belgrade). Since its founding, the population of the city has been constantly increasing. According to the 1991 census, 56.2% of the people who came to Novi Sad from 1961 to 1991 were from other parts of Vojvodina, while 15.3% came from Bosnia and Herzegovina and 11.7% from Central Serbia.

According to the last official census from 2002, the city's urban population was 216,583 and 299,294 with the surrounding inhabited places of the municipalities included. According to estimation from the end of 2004, there were 306,853 inhabitants in the city municipal area (estimation published on 31 December 2004 by the statistical office of Serbia). From city's registry estimation in December 2009, population of the urban area of Novi Sad was 284,426, and the population of municipal area was at 370,757.[20] The city has an urban population density of 1,673.7/km² (4,340.3/sq mi) - census 2002.

Most of the inhabited places in the municipalities have an ethnic Serb majority, while the village of Kisač has an ethnic Slovak majority.

Economy

Novi Sad is the economic centre of Vojvodina, the most fertile agricultural region in Serbia. The city also is one of the largest economic and cultural centres in Serbia and former Yugoslavia.Novi Sad has 3.621.012 square meters of office space.[21]

Novi Sad had always been a relatively developed city within Yugoslavia. In 1981 Novi Sad's GDP per capita was 172% of the Yugoslav average.[22] In the 1990s, the city (like the rest of Serbia) was severely affected by an internationally imposed trade embargo and hyperinflation of the Yugoslav dinar. The embargo and economic mismanagement lead to a decay or demise of once big industrial combines, such as Novkabel (electric cable industry), Pobeda (metal industry), Jugoalat (tools), Albus and HINS (chemical industry). Practically the only viable remaining large facility is the oil refinery, located northeast of the town (along with the thermal power plant), near the settlement of Šangaj.

The economy of Novi Sad has mostly recovered from that period and it has grown strongly since 2001, shifting from industry-driven economy to the tertiary sector. The processes of privatization of state and society-owned enterprises, as well as strong private incentive, increased the share of privately-owned companies to over 95% in the district, and small and medium-size enterprises dominated the city's economic development.[23]

The significance of Novi Sad as a financial center is proven by numerous banks such as Vojvođanska Bank, Erste Bank, Kulska Bank, Meridian Bank, Metals Bank, NLB Continental Bank and Panonska Bank;[24] and second largest insurance company in Serbia - DDOR Novi Sad. The city is also home to the state-owned oil company - Naftna Industrija Srbije. It is also the seat of the wheat market.

At the end of 2005, Statistical office of Serbia published a list of most developed municipalities in Serbia, placing City of Novi Sad at No.7 by national income, behind some Belgrade municipalities and Bečej, with 201.1% above Serbia's average.[25]

Society and culture

In the 19th century, the city was the capital of Serbian culture, earning the nickname Serbian Athens. In that time, almost every Serbian novelist, poet, jurist, and publicist at the end of 19th century and at the beginning of 20th century had lived or worked in Novi Sad some time of his or her career. Among others, these cultural workers include Vuk Stefanović Karadžić, Mika Antić, Đura Jakšić, etc. Matica srpska, the oldest cultural-scientific institution of Serbia, was moved from Budapest to Novi Sad in 1864, while Serbian National Theatre, the oldest professional theatre among the South Slavs, was founded in Novi Sad in 1861.

Today, Novi Sad is the second cultural centre in Serbia (besides Belgrade) and city's officials try to make the city more attractive to numerous cultural events and music concerts. Since 2000, Novi Sad is home to the EXIT festival, the biggest music summer festival in Serbia and the region; and also the only festival of alternative and new theatre in Serbia - INFANT, most prominent festival of children's literature - Zmaj Children Games, International Novi Sad Literature Festival, Sterijino pozorje, Novi Sad Jazz Festival, and many others.[26] Besides Serbian National Theatre, the most prominent theatres are also Youth Theatre, Cultural centre of Novi Sad and Novi Sad Theatre. Novi Sad Synagogue also houses many cultural events in the City. Other city's cultural institutions include Offset of the Serbian Academy of Science and Art, Library of Matica Srpska, Novi Sad City Library and Azbukum. City is also home to cultural institutions of Vojvodina: Vojvodina Academy of Science and Art and Archive of Vojvodina, which collect many documents from Vojvodina dating from 1565.

Museums and galleries

City has a couple of museums, and many galleries, public and privately owned through Novi Sad. The most well known museum in the city is Museum of Vojvodina, founded by Matica srpska in 1847, which houses a permanent collection of Serbian culture and a life in Vojvodina through history. Museum of Novi Sad in Petrovaradin Fortress has a permanent collection of history of fortress.

Gallery of Matica Srpska is the biggest and most respected gallery in the city, which has two galleries in the city centre. There is also The Gallery of Fine Arts - Gift Collection of Rajko Mamuzić and The Pavle Beljanski Memorial Collection - one of the biggest collections of Serbian art from 1900s until 1970s.

Education

Novi Sad is one of Serbian most important centers of higher education and research, with four universities and numerous professional, technical, and private colleges and research institutes, including a law school with its own publication.

Novi Sad is home to two universities and seven private faculties.[27] The largest educational institution in the city is the University of Novi Sad with approximately 38,000 students and 2,700 in staff. It was established in 1960 with 9 faculties in Novi Sad of which 7 are situated in modern university campus. There are also Novi Sad Open University and Novi Sad Theological College in the city.

In Novi Sad there are 36 elementary schools (33 regular and 3 special) with 26,000 pupils.[28][29] The secondary school system consists of 11 vocational schools and 4 grammar schools with almost 18,000 students.[29][30]

Folk and art

Novi Sad has dozens of culture and art societies. They are well known representatives of multicultural life in Novi Sad all over the world. Usually taken form in name for culture and art society is KUD (Kulturno Umetnicko Drustvo). The most well known societies in the city are: KUD Svetozar Markovic, AKUD Sonja Marinkovic, SKUD Zeljeznicar, FA Vila and the oldest - established in 1900. SZPD Neven. They are open for all citizens.

National minorities exposes their own tradition, folklore and songs in Hungarian MKUD Petőfi Sándor, Slovakien SKUD Pavel Jozef Safarik, Rutenian RKPD Novi Sad, Bulgarian, Slovenian Jewish, Croatian and other societies.

Media and publishing

Novi Sad has two major daily newspapers, Dnevnik and Građanski list, both in Serbian. Until 2006, Magyar Szó, a newspaper in Hungarian, had its headquarters in Novi Sad, but it was moved to Subotica. The city is home to the main headquarters of the regional public broadcaster Radio Television of Vojvodina - RTV and city's public broadcaster Apolo, as well as a few commercial TV stations, Kanal 9, Panonija and Most. Novi Sad has many local commercial radio stations, dominant being Radio 021 and Radio As.

Novi Sad is also known as a center of publishing. The most prominent publishers are Matica srpska, Stilos, Prometej, Zoran Stojanovic’s publishing house, IP Adresa IP Adresa, etc. There few well-known journals in literature and art: Letopis Matice srpske Letopis matice srpske, the oldest Serbian Journal; Polja Polja, issued by Cultural Center of Novi Sad and Zlatna greda, which is issued by the Association of Writers of Vojvodina Association of Writers of Vojvodina.

Tourism

The number of tourists started to increase since the year 2000, when Serbia started to open to Western Europe and the United States. Every year, in the beginning of July, during the annual EXIT music festival, the city is full of young people from all around Europe. In 2005, 150,000 people visited this festival, which put Novi Sad on the map of summer festivals in Europe.[32] Besides EXIT festival, Novi Sad Fair attract many business people into the city; in May, the city is home to the biggest agricultural show in the region, which 600,000 people visited in 2005.[33] There is also a tourist port near Varadin Bridge in the city centre welcoming various river cruise vessels from across Europe who cruise on Danube river.

The most recognized structure in Novi Sad is Petrovaradin Fortress, which dominates the city and with scenic views of the city. Besides the fortress, there is also historic neighborhood of Stari Grad, with many monuments, museums, caffes, restaurants and shops. There is also a National Park of Fruška Gora nearby, approx. 20 km from city centre.

Sport

Sports started to develop in 1790 with the foundation of "City Marksmen Association". However, its serious development started after the establishment of the Municipal Association of Physical Culture in 1959 and after 1981, when Spens Sports Center was built. Today, about 220 sports organizations are active in Novi Sad.[34] Novi Sad is the second best developed sports city in Serbia (after Belgrade).

The most popular sport in the city is definitely football. There are many football pitches in Novi Sad's neighborhoods, as well as in every town and village in the suburbs. Besides FK Vojvodina, which is in the first league, there are many smaller clubs in the national second and third league. Most well known are: FK Novi Sad, FK Kabel, FK Mladost, FK Slavija Novi Sad, etc.

Citizens of Novi Sad participated in the first Olympic Games in Athens. The largest number of sportsmen from Novi Sad participated in the Atlanta Olympic Games – 11, and they won 6 medals, while in Moscow – 3, and in Montreal and Melbourne – 2.[34]

Novi Sad was the host of the European and World Championships in table tennis in 1981,[35] 29th Chess Olympiad in 1990, European and World Championships in sambo, Balkan and European Championships in judo, 1987 final match in the Cup winners cup of European Basketball[35][36] and final tournament of the European Cup in volleyball.[35] Apart from that Novi Sad is the host of the World League in volleyball and traditional sport events such as Novi Sad marathon, international swimming rally and many other events. Between the 16 and 20 September 2005, Novi Sad co-hosted the 2005 European Basketball Championship.[35]

| Club | Sport | Founded | League | Venue |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FK Vojvodina | Football | 1914 | Meridian Superliga | Karađorđe Stadium |

| KK Vojvodina | Basketball | 2000 | Sinalco Superleague | Spens Sports Center |

| KK Novi Sad | Basketball | 1985 | Sinalco Superleague | Spens Sports Center |

| OK Vojvodina | Volleyball | 1946 | Serbian volley league | Spens Sports Center |

| HK Vojvodina | Hockey | 1957 | Serbian Hockey League | Spens Sports Center |

| HK Novi Sad | Hockey | 1998 | Serbian Hockey League | Spens Sports Center |

Hk Vojvodina hosted the first hockey competitions in the region. Founded by visiting Czech students, the team and youth program continues since 1957. During this time HK vojvodina has captured 6 Yugoslavia/Serbia Champions Cup at the senior level. Recently, in March 2009, the club has won the Panonian league, representing the champion of Serbia/Croatia. A terrible fire tore through the Spens Sports Center after the championship win, resulting in the loss of all equipment. The club has used the friendship built between Canadian hockey teams and players. At the Div II World Championships hosted by Hk Vojvodina in NoviSad, 7 players from the club represented Serbia. Serbia won the gold medal and have been promoted to the Division I level for 2010.

Recreation and leisure

Apart from the culture of attending sports events, people from Novi Sad participate in a wide range of recreational and leisure activities. Football and basketball are the most popular participation team sports in Novi Sad. Cycling is also a very popular in Novi Sad. Novi Sad's flat terrain and extensive off-road paths in the mountainous part of town, in Fruška Gora is conducive to riding. Hundreds of commuters cycle the roads, bike lanes and bike paths daily.

Proximity to the Fruška Gora National Park attracts many people from the city on weekends in many hiking trails, restaurants and monasteries on the mountain. In the first weekend of May, there is a "Fruška Gora Marathon", with many hiking trails for hikers, runners and cyclists.[37] During the summer, there is Lake of Ledinci in Fruška Gora, but also there are numerous beaches on the Danube river, the largest being Štrand in the Liman neighborhood. There are also a couple of small recreational marinas on the river.

Infrastructure

Novi Sad is connected by motorway to Subotica and Zrenjanin, by highway to Belgrade; and by railroad to major European cities, such as Vienna, Budapest, Kiev and Moscow. One of the most famous structures in the city are the bridges over river Danube, which were destroyed in every war and then rebuilt. The city is about 90 minutes drive from Belgrade Nikola Tesla Airport, which connects it with capitals across Europe.

Public transportation

The main public transportation system in Novi Sad consists of bus lines. There are twenty-one urban lines and twenty-nine suburban lines. The operator is JGSP Novi Sad, with its main bus station at the start of Liberation Boulevard. In addition, there are numerous taxi companies serving the city. The city used to have a tram system, but it was disassembled in 1958.

See also

- Novi Sad Fair

- NATO bombing of Novi Sad in 1999

- List of people from Novi Sad

- List of places in Serbia

- List of cities, towns and villages in Vojvodina

References

Bibliography

- Boško Petrović - Živan Milisavac, Novi Sad - monografija, Novi Sad, 1987

- Milorad Grujić, Vodič kroz Novi Sad i okolinu, Novi Sad, 2004

- Jovan Mirosavljević, Brevijar ulica Novog Sada 1745-2001, Novi Sad, 2002

- Jovan Mirosavljević, Novi Sad - atlas ulica, Novi Sad, 1998

- Mirjana Džepina, Društveni i zabavni život starih Novosađana, Novi Sad, 1982

- Zoran Rapajić, Novi Sad bez tajni, Beograd, 2002

- Đorđe Randelj, Novi Sad - slobodan grad, Novi Sad, 1997

- Enciklopedija Novog Sada, sveske 1-26, Novi Sad, 1993–2005

- Radenko Gajić, Petrovaradinska tvrđava - Gibraltar na Dunavu, Novi Sad, 1994

- Veljko Milković, Petrovaradin kroz legendu i stvarnost, Novi Sad, 2001

- Veljko Milković, Petrovaradin i Srem - misterija prošlosti, Novi Sad, 2003

- Veljko Milković, Petrovaradinska tvrđava - podzemlje i nadzemlje, Novi Sad, 2005

- Veljko Milković, Petrovaradinska tvrđava - kosmički lavirint otkrića, Novi Sad, 2007

- Agneš Ozer, Petrovaradinska tvrđava - vodič kroz vreme i prostor, Novi Sad, 2002

- Agneš Ozer, Petrovaradin fortress - a guide through time and space, Novi Sad, 2002

- 30 godina mesne zajednice "7. Juli" u Novom Sadu 1974-2004 - monografija, Novi Sad, 2004

- Branko Ćurčin, Slana Bara - nekad i sad, Novi Sad, 2002

- Branko Ćurčin, Novosadsko naselje Šangaj - nekad i sad, Novi Sad, 2004

- Zvonimir Golubović, Racija u Južnoj Bačkoj 1942. godine, Novi Sad, 1991

- Petar Jonović, Knjižare Novog Sada 1790-1990, Novi Sad, 1990

- Petar Jonović - Dr Milan Vranić - Dr Dušan Popov, Znameniti knjižari i izdavači Novog Sada, Novi Sad, 1993

- Ustav za čitaonicu srpsku u Novom Sadu, Novi Sad, 1993

- Sveske za istoriju Novog Sada, sveske 4-5, Novi Sad, 1993–1994

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 "Statistike iz opštih podataka" (in Serbian). JP Informatika. http://www.nsinfo.co.rs/?q=node/54. Retrieved 2010-08-13. Novi Sad proper, Petrovaradin and Sremska Kamenica included in total urban population.

- ↑ [1], "Official page of government of Vojvodina", 12 November 2009

- ↑ (in Serbian) Popis stanovništva, domaćinstava i Stanova 2002. Knjiga 1: Nacionalna ili etnička pripadnost po naseljima. Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. 2003. ISBN 86-84443-00-09.

- ↑ "Municipalities of Serbia, 2006". Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. http://webrzs.stat.gov.rs/axd/Zip/OG2006webE.zip.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Branko Ćurčin, Slana Bara nekad i sad, Novi Sad, 2002.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Borovszky Samu: Magyarország vármegyéi és városai, Bács-Bodrog vármegye I.-II. kötet, Apolló Irodalmi és Nyomdai Részvénytársaság, 1909.

- ↑ Đorđe Randelj, Novi Sad slobodan grad, Novi Sad, 1997.

- ↑ David Cesarani (1997). Genocide and Rescue: The Holocaust in Hungary 1944. Berg Publishers. p. 13. ISBN 1859731260. http://books.google.com/?id=HrK8B0VpFBkC&pg=PR7. Retrieved 2009-08-04.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Enikő A. Sajti (Spring 2006). "The Former 'Southlands' in Serbia: 1918- 1947". The Hungarian Quarterly XLVII (181). http://www.hungarianquarterly.com/no181/9.html. Retrieved 2009-08-04.

- ↑ Večernje Novosti, Utorak, 9. Jun 2009, strana 11, mapa masovnih grobnica u Srbiji.

- ↑ Mészáros Sándor (1995.). Holttá nyilvánítva - Délvidéki magyar fátum 1944-45.. Hatodik Síp Alapítvány.

- ↑ Cseres Tibor (1991). Vérbosszú Bácskában. Magvető kiadó.

- ↑ Dr. Szántó Konrád OFM. (1991). "A meggyilkolt katolikus papok kálváriája". Mécse Kiadó. http://franka-egom.ofm.hu/irattar/irasok_gondolatok/konyvismertetesek/konyvek_5/meggyilkolt_katolikus_papok/02_fejezet.htm. Retrieved 2009-08-04.

- ↑ Data from Serbian Statistical Office

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Geographical location of Novi Sad

- ↑ Завод за урбанизам: "Еколошки Атлас Новог Сада" ("Ecological Atlas of Novi Sad"), page 14-15, 1994.

- ↑ Climate in Novi Sad

- ↑ "Weather data for Rimski Šančevi-Novi Sad" (in (Serbian)). Republic Hydrometeorological Service of Serbia. http://www.hidmet.gov.rs/ciril/meteorologija/stanica_sr.php?moss_id=168. Retrieved 1961-1990.

- ↑ "List of Twin Towns in the Ruhr District". © 2009 Twins2010.com. http://www.twins2010.com/fileadmin/user_upload/pic/Dokumente/List_of_Twin_Towns_01.pdf?PHPSESSID=2edd34819db21e450d3bb625549ce4fd. Retrieved 2009-10-28.

- ↑ Information taken from official JP Informatika website

- ↑ "statistike iz opštih podataka |". Nsinfo.co.rs. http://www.nsinfo.co.rs/?q=node/54. Retrieved 2009-06-16.

- ↑ Radovinović, Radovan; Bertić, Ivan, eds (1984) (in Croatian). Atlas svijeta: Novi pogled na Zemlju (3rd ed.). Zagreb: Sveučilišna naklada Liber.

- ↑ Regional Chamber of Commerce Novi Sad, Basic data

- ↑ National Bank of Serbia - List of Banks operating in Serbia.

- ↑ Municipalities of Serbia for 2005 ISSN-1452-4856.

- ↑ Cultural events calendar

- ↑ Ministry of education, list of private universities and faculties

- ↑ List of elementary schools in Novi Sad

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Serbian statistical office

- ↑ List of secondary schools

- ↑ NEVEN

- ↑ History of EXIT festival

- ↑ About agricultural fair in 2006 (in Serbian)

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Sport in Novi Sad, City official site

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 Најзначајније приредбе

- ↑ Cup Winners’ Cup 1986-87

- ↑ Fruška Gora Marathon

External links

- Novi Sad - Official site (Serbian) (English)

- City's assembly - Official site (Serbian)

- Virtual tours through Novi Sad

- Novi Sad - Interactive Map

- Novi Sad travel guide from Wikitravel

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||